The Automatic Dynamic Functioning

And humans as technological device

Were you captivated, enchanted even, by Paul Kingsnorth’s writing on The Machine a few years back here on Substack? I was. I had a paid sub for a while and printed out all the essays, nodding along all the while, seeing that the creeping, left-brain disease of modernity was the cause of all our problems, and a return to traditional lifeways, luddism and olde worlde values in every sense was where sanity lay.

It was one phase among many on a winding path of collapse acceptance, with various stop offs or detours, that had to be explored it seems.

A more significant milestone some years later was the writing of John Gray in ‘Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals. After reading this book I saw through the humanist spell that Kingsnorth cast, and since then I have lost the anguish and nostalgic longing that his writing evoked.

Instead I was newly shaped by the deep-time insight and wisdom that these few elegant paragraphs below imparted.

John Gray sees that humans and all Earth’s creatures are machine-like in their functioning. He first illustrates how the natural world is machine-like with this example:

“The industry undertaken by some leaf-cutter ants is close to farming. They excavate large underground nests which the colony inhabits. Workers go out foraging for leaves which they cut with their jaws and bring back to the nest. These leaves are used to grow colonies of fungi, enzymes which can digest the cellulose cell walls of the leaves and render them suitable for eating by the colony. The garden is vital for the ants’ survival; without the continuous farming and feeding of the fungal colonies, the ant colony is doomed. These ants are indulging in an agricultural enterprise which they systematically maintain.” (*John Gray: Straw Dogs)

Gray then compares the industrial practice of ant farming to human agricultural practice that eventually led to the modern cities of today. He sees that these cities evolved for humans in the same way that ant colonies evolved for ants, or bee hives function for bees:

“Cities are no more artificial than the hives of bees. The Internet is as natural as a spider’s web. As Margulis and Sagan have written, we are ourselves technological devices, invented by ancient bacterial communities as means of genetic survival: ‘We are a part of an intricate network that comes from the original bacterial takeover of the Earth. Our powers and intelligence do not belong specifically to us but to all life.’

Thinking of our bodies as natural and of our technologies as artificial gives too much importance to the accident of our origins. If we are replaced by machines, it will be in an evolutionary shift no different from that when bacteria combined to create our earliest ancestors.”

So this is a vastly different perspective from Kingsnorth, who sees The Machine take over of the Earth as fundamentally wrong, an aberration or ‘freak of nature’.

Gray continues, explaining exactly how he defines humanism and what this foundational belief results in:

“Humanism is a doctrine of salvation – the belief that humankind can take charge of its destiny. Among Greens, this has become the ideal of humanity becoming the wise steward of the planet’s resources. But for anyone whose hopes are not centred on their own species, the notion that human action can save themselves or the planet must be absurd. They know the upshot is not in human hands. They act as they do, not out of the belief that they can succeed, but from an ancient instinct.”

This ancient instinct is in stark contrast to the modern, techno-optimist environmentalist (which Kingsnorth railed against as well), and Gray goes on to explain that this ancient instinct is biophilia, a love for the Earth:

“For much of their history and all of prehistory, humans did not see themselves as being any different from the other animals among which they lived. Hunter-gatherers saw their prey as equals, if not superiors, and animals were worshipped as divinities in many traditional cultures. The humanist sense of a gulf between ourselves and other animals is an aberration. It is the animist feeling of belonging with the rest of nature that is normal. Feeble as it may be today, the feeling of sharing a common destiny with other living things is embedded in the human psyche. Those who struggle to conserve what is left of the environment are moved by the love of living things, biophilia, the frail bond of feeling that ties humankind to the Earth.”

While Gray recognises that some are driven by biophilia, to love and protect what’s left of the Earth, these people are very much a tiny minority. He sees that the vast majority of mankind are:

‘ruled not by its intermittent moral sensations, still less by self-interest, but by the needs of the moment.’

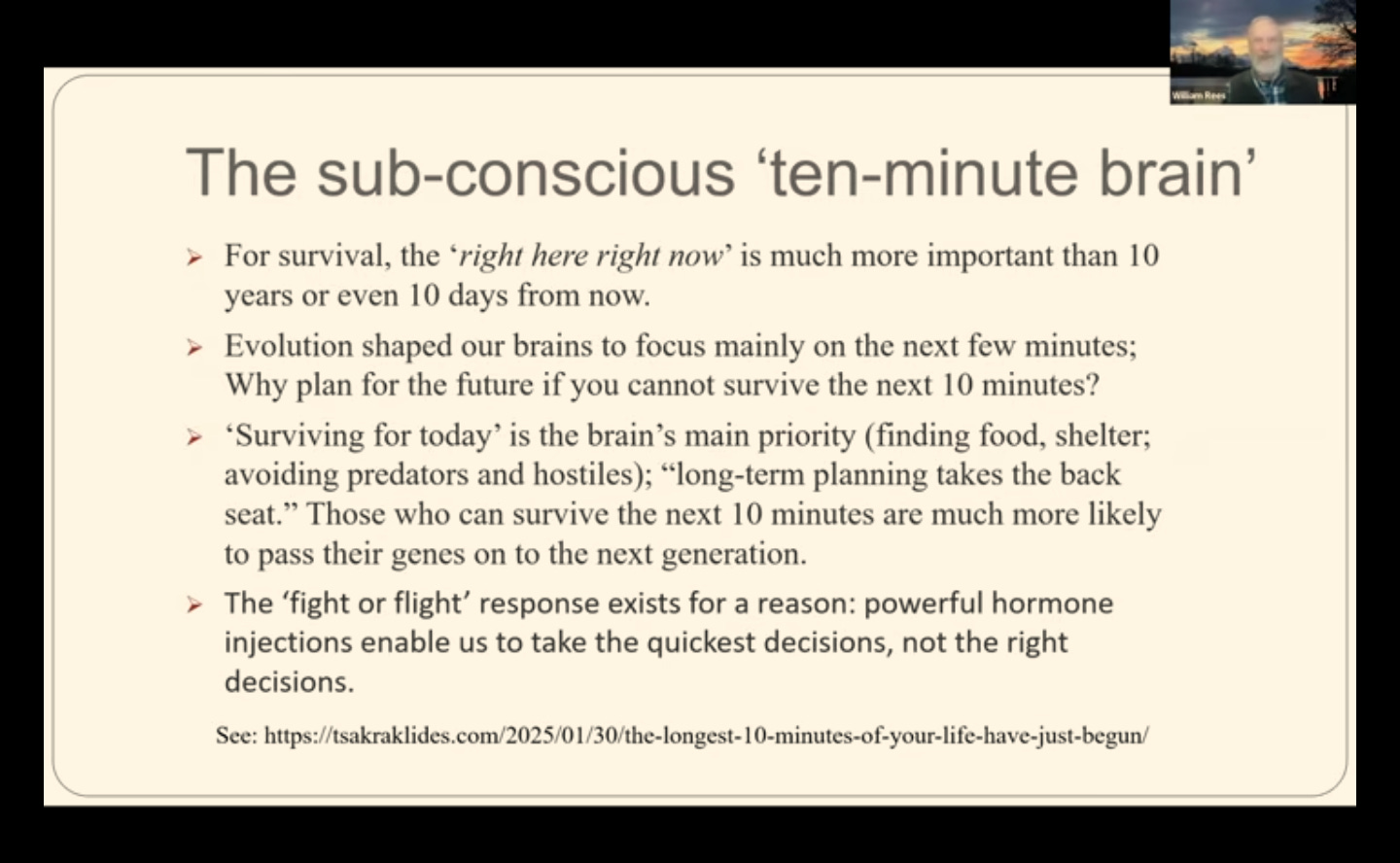

And here George Tsakraklides’s concept of the ‘10 minute brain’, as captured by William E Rees in this talk at CACOR, comes into play. It’s all about what I feel like and want now, or in the next ten minutes, and there are powerful evolutionary forces that explain why this is, as the talk unpacks.

Gray concludes, in this small chapter called Green Humanism, that as a species we seem:

“fated to wreck the balance of life on Earth and thereby to be the agent of its own destruction. What could be more hopeless than placing the Earth in the charge of this exceptionally destructive species? It is not of becoming the planet’s wise stewards that Earth-lovers dream, but of a time when humans have ceased to matter.”

And this was written back in 2003, a man ahead of his time.

I put myself in this camp, dreaming of a time when humans cease to matter and when the Earth will eventually recover. This biophilia, embedded in the human psyche, emerges in different ways for different people. It explains our love of our pets, one of the few ways we moderns now have of connecting with our other-than-human kin.

It’s not that humans are not included in biophilia, love for humans is part of it too, but at some stage, the human species has broken off from the tree of life and has ceased to function like a species. And this happened a lot further back than you might imagine, see my friend Paqnation’s essay here on the ways that fire forever changed us.

So the idea that humans are like a kind of technological device is most likely quite off putting to most people. And when this idea of existence being machine-like is conjured up, it really only makes sense when it is considered in relation to its opposite, of life being organic, a flow, or a River-of-Life.

So whether automatic and machine-like, or organic and flowing, it describes the same unexplainable happening we know of here as simply Life.

Seeing my origin as part of a great automatic dynamic functioning, where I am playing out my programming as a tiny, infinitesimally small part of this huge world wide web of existence, is where I have landed for now.

It means I am not living in nostalgic pining of a time-gone-by nor dreading a futuristic machine take over. Although tender feelings, or an ache or melancholy still arise unbidden at times, there is no story running to frame it, so it comes and goes as it must.

We are in collapse, of course AI and The Machine Age is going to reach a fever peak before it disappears, then when it does, we will have even bigger issues to worry about.

“Technology is not something that humankind can control. It is an event that has befallen the world. Once a technology enters human life – whether it be fire, the wheel, the automobile, radio, television or the Internet – it changes it in ways we can never fully understand.

‘Can you believe it!? AI is taking our jobs, destroying water sheds, and eating up all the electricity!’

Yawn, yes I can believe it.

Hat tip to Karen Perry and the 6th benefit of collapse acceptance -

6) Calm Grounding - not disrupted by catastrophic information.

*All block quotes are from the book:

Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals by John Gray

Great essay Renaee!